A few years ago, I was commissioned to translate Esquisse pour le théâtre II (Rough for Theatre II) by the Irish bilingual writer Samuel Beckett, definitely the least staged and probably the least read dramatic piece among his work. Thanks to this translation, I have become more forensic than ever about the proper names in his writing, because this piece, unlike Beckett’s other dramatic pieces, contains many and peculiar proper names.

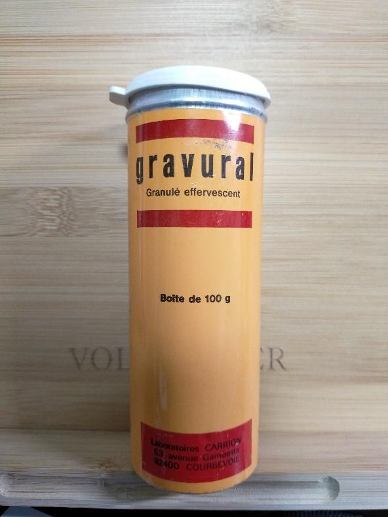

It took a long time but I managed to search the etymology and implications of most of the names, except for one: the name “gravural” in the French version of this dramatic piece. I gave up on the search for a while but one day a whim led me to google images with the word and I came across an online antique shop with a photograph of a cylindrical container with the letters “gravural” printed on the orange chipped background. Below the name read “granulé effervescent”, that is to say that the tin contains soluble medicine. Though I could see more letters printed below this phrase, the resolution of the image was too low to decipher. Without further ado, I clicked to purchase this item.

It turned out that the tin contains medicine for acid urine and urinary stones. This has only led to a further conundrum concerning the interpretation of this play.

Beckett, who removes any unnecessary stuff from his writing' would be laughing at me: No addition, but merely reduction!

**

There is a character who is forced to act altruistically with the assistance of “things as medium” in Beckett’s writing. His name is Clov, and he is the character in the play Fin de partie/Endgame (1957). Of all four characters, he is the only one who can walk. The other three are Hamm, his stepfather and the main character, who is blind and lives in a wheelchair that he cannot move by himself, Nagg and Nell, seemingly Hamm’s parents, who are miserably in “the ashbin”.

Clov is in a chamber off-stage, invisible from the audience. Hamm whistles to call for Clov when he needs him and gives him orders. Clov grumbles and resists at times, though in the end he acts as commanded. Hamm loathes Clov’s odour and does not have him near unless necessary. In other words, Clov’s obedience is displayed mostly by his operation on things as medium. When Hamm tells Clov to feed Nagg and Nell, he brings them something. When Hamm wants to know the weather, Clov is back on stage with a “telescope” and “steps” to look out from the windows located both upper right and left on stage, knowing that there is nothing but “grey” outside the windows. When Hamm is shaken by the presence of a flea, Clov cleanses the stage with insecticide.

Theoretically speaking, Fin de partie/Endgame suggests that this play continues forever as long as Hamm orders and Clov carries them out with the assistance of “things”. They are perfectly aware of it and Clov is fed up with his own obedience. Hamm asks Clov repeatedly why his adopted son does not kill him, why he does not stop playing. However, Hamm’s words sound merely cynical to Clov’s ears, who understands that he sustains the lives of the others on stage. Presence and traffics of “things” are a matter of life and death of the characters in this play.

Regardless of the mind-game between Hamm and Clov, “things as medium” between them are slowly reduced and disappear for unexplained reasons. Symptoms of such reductions are already palpable at the beginning of the play. There is no more “pup”, and instead a biscuit is provided. Distribution of sugar-plums promised by Hamm to Nagg is delayed and never happens. The same pattern applies to Hamm’s painkiller, whose stock is announced to be “no more” toward the end. There is “no more coffin” for Hamm to be in. Or perhaps, the logic of “no more” here may be forged, like a bicycle Clov wanted but never owned as a child, and there is “no more bicycle” now.

Reduction or ultimate disappearance of “things as medium” corresponds to the failure in their relationship sustained chiefly by a series of habits, an eternal loop of orders and exertions. Toward the end of the play, they exchange awkward greetings of farewell and Clov leaves the stage. When he comes back to be viewed by the audience in the outfits for travelling, he remains but no longer responds to Hamm. Hamm removes a whistle from his neck, throws it on the floor and calls for Nagg. No reply follows. This sequence appears to satisfy Hamm who says “Bon/Good” before he begins his soliloquy, covers his blood-stained handkerchief or “old stancher”, the same as he was at the beginning of the play. Meanwhile, Clov remains motionless and emotionless, looking at Hamm. The curtain closes.

Focusing on “things as medium” in Fin de partie/Endgame reveals that “things” in this play are mostly functional, present for the purpose of exchanges between Hamm and Clov. Yet, Beckett’s plays that follow Endgame display different features. In Krapp’s Last Tape, the piece written after Fin de partie/Endgame, things can turn against the main character Krapp. A tape recorder is on the desk for him to replay his past recordings, but he is constantly disturbed by their content because he cannot easily identify the part he wishes to listen to. A banana is there for him to suck and meditate on but he leaves its skin on the floor and slips on it. Here, “things” still trigger some happenings. Happy Days, the play of two acts, attests to things that change their nature. In Act 1, they are laid out in front of the main character Winnie who is buried up to the waist in the mound. The “things” are used in Winnie’s daily rituals (a parasol, a toothbrush, a hairbrush, a mirror, etc.). What stands out in this play, is that things gain another function in Act 2 when Winnie is buried up to the shoulders and is no longer able to use her hands. Then, things are transformed into the reminder of her everyday ritual in the past, of the fact that it is “no longer” possible, that her familiar everyday is lost. In fact, there are very few props used in Beckett’s plays after Happy Days, let alone “un-”functional stuff.

In view of “function”, things as the reminder of the past do not have use value. They become unnecessary. By clearing unnecessary stuff from space, it becomes cleaner and more manageable, and in Beckett’s case, more abstract, which was the direction his plays were took from the 1960s onward. However, pleasure and satisfaction drawn from creating manageable space would succumb to the temptation to design efficient space that may exclude the potential of excess, unnecessity, and un-expectedness; from the beginning the space would not tolerate even a flea or traces of the past. Beckett does try to retain traces in his later works but they take a form very different from the concrete “things as medium” in Fin de partie/Endgame.

Our society is experiencing cultures where people are encouraged to keep their space clean by decluttering (danshari) and by preparing for the end of one’s life (shukatsu). I would not deny the importance of putting things in order but at the same time I would like to advocate for the presence of “unnecessary stuff”, precisely for their potential in spacing the space dictated solely by use value. Only this spacing can invite chances, both fortunate and unfortunate, and encounters with unexpected others. “Things” whose use value is stripped bare may be unnecessary but they can become a witness to a fragment of our past, the past that can be so easily obliterated, and also to our forgetfulness.

Hence, you would now understand why it is reasonable that an untidy person such as me has to place a rather high expectation on this little antique tin as a possible witness of what Beckett set against himself.