Pulling at a thread that dangles near the end of the previous モノtext, I’m thinking more about instruments – this time not any one of them in particular, but all of the things we make music with, and what they afford us, individually and communally.i

Most but not all cultures have instruments; those that do not use the body as an instrument for making music (not only the vocal cords, but the external body - in organology called a corpophone). Before the dissemination of Western music across the globe, instruments were almost inseparable from the places and people that created them, as most were made from local materials in response to local climates and local ways of life. Now the standard Western acoustic instruments – pianos, violins, guitars, saxophones - are made on one continent for sale and use on others, and we can move between countries and climates with them, making comparatively little adjustment.

Under pre-industrial conditions instruments are generally made by the people who play them, so the makers experience the sound-making device as the fruit of their own labour. Most of us, however, obtain instruments as commodities whose primary value is to enhance pleasure in our daily lives, those of our household members, and members of our various (face-to-face and virtual) communities. When we learn to play, at first we stumble and struggle with the instrument, finding everything strange and awkward while our bodies, and most of all our hands, learn new patterns of motion. If we persist, there comes a moment of fusion between human things and the music thing; then we hold and manipulate the instrument as naturally as we do implements to feed and sustain ourselves. And we protect our instruments as naturally as we do our offspring. Once that fusion occurs, we don’t want to let go – we want to play as often as possible, and we experience discomfort during stretches of time passed without being able to play. Moreover we don’t want to part with our instruments – we tend to keep them close by, certain that we will play them just as much as we have in the past, and unrealistically hopeful that we will play just as well again.

In my own experience, I have yet to ‘let go’ of any instrument that I’ve played since my early teens.Over about half a century I’ve learned cello, guitar, 琵琶, 三線, 笙, 竜的 and 篠笛. Of those, the only instrument I no longer have in my home (or office, as there’s more room there!) is the cello, simply because I learned it for just two years as a child on a half-size instrument borrowed from my teacher. Most of the instruments I’ve played are Japanese traditional ones, but I’ve taken them from Japan to regional New England in Australia (500 kms away from Sydney) where I lived for over 10 years, then transported all of them back here to Japan with me, so they’d be at hand whenever I wanted to play them.

I’ve spent most time playing guitars and biwa(s) – I have several forms of both. But the one I cannot be without under any circumstances is my Marcelino Lopez guitar, for it was the first instrument I immersed myself in playing. Newly made in Madrid then carried to Australia by my mother 48 years ago (in those innocent days when instruments could be stowed in the long coats cupboard on a 747 jet), my teenage body grew with it, its sound becoming richer as the woods ‘settled’ and as my fingers settled into ways of coaxing out a palette of tone colours and voicings. Even now when my fingers no longer work well because of age and the effects of a recent injury, I take the Lopez guitar out of its case, smell it (for the aroma of those long-settled woods, too, has deepened over decades), and play it whenever I can find time. Only death will part us, and I’ve already bequeathed it to a close relative in my will.

What are instruments for? In modern Japanese they are called 楽器. The 楽 in 楽器 of course is the same one in ‘oto no raku’/音楽/lit.’ pleasure in/of/from sound – the most common word for music since the Meiji era. But who is that ‘sonic pleasure’ or ‘pleasurable sound’ intended for? Who do players of instruments make them (re)sound for?

In the first instance for themselves. Musicians performing music that they themselves don’t find ways to enjoy tend to play poorly, and if they don’t give full attention to the sounds they are making the music loses its way, its flow and coherence. Yet we play alone not only for the intrinsic pleasure of it; we also play to keep ourselves well. Playing an instrument can be physically very demanding – in itself almost a workout in the case of some drums (think of wadaiko, for instance) or large instruments one must stand to play, such as double bass. However, what I have in mind is the emotional effects of focussed playing during which players reach a flow state, their minds and bodies engaged solely with the music. There are empirically-demonstrated physiological and psychological benefits for well-being/wellness that come from such immersive engagement with an instrument, regardless of whether anyone else is around to hear and see the performance.

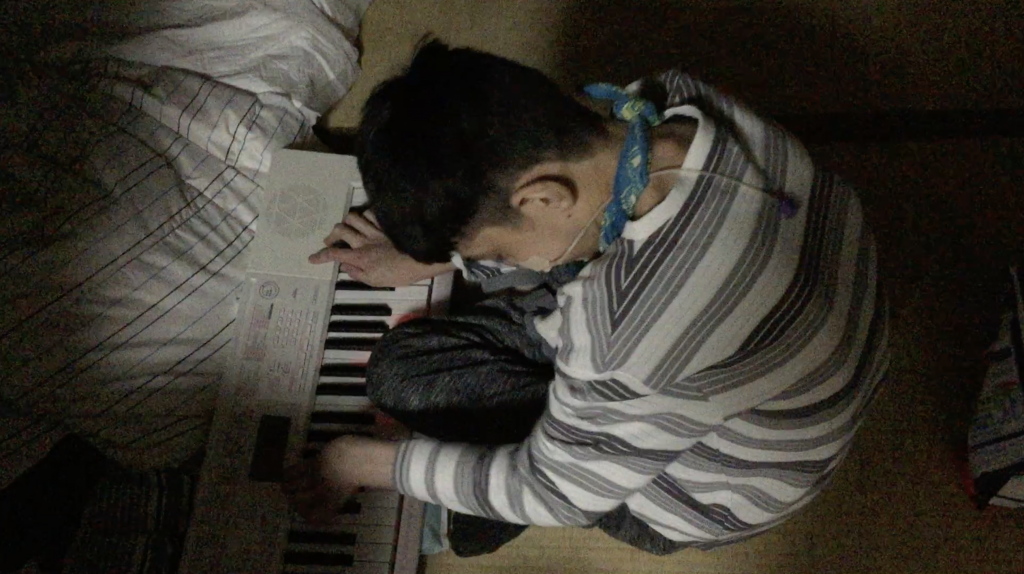

Those benefits are there for all human beings, regardless of their cognitive or physical abilities or “disabilities”. I have seen that countless times in daily life as I watch my son Claudio Yoshiyuki, who’s now twenty. He was born with an extreme degree of disability and is helpless in most regards; to be sure, he would die within 24 hours if no one were there to care for him. Yet in addition to many sessions of formal music therapy in the pre-Covid years, Claudio has made music at home and at the ゆかりの木 daytime facility he attends on weekdays. He is non-verbal and probably has no “understanding” of music as anything but play and enjoyment. He cannot control his hands well enough to learn to play a single composed/fixed tune, even though he recognises many tunes and insistently touches the mouth of a carer (or parent) until s/he sings, hums or whistles that tune. He has no playing “technique” at all (in the sense that that word is usually used, to refer to skill acquired through persistent practice), but he makes music for long stretches of time, immersing himself in both the sounds and the somatic and haptic experiences afforded by his many “instruments”, which include miscellaneous informal rattles and shakers he discovers among his toys or objects he encounters, as well as a simple electric keyboard. On the Casio keyboard he deliberately hits the black keys (originally perhaps because they are easier for his fingers to depress) in regular rhythm and pitch patterns, but he also seems to enjoy injecting more “astringent” colours by occasionally touching adjacent white keys so as to produce half tones. Claudio also sings (or moans) some of the time – not quite in the manner of Keith Jarett or Pablo Casals, but no less intensely – as he plays.

Claudio-Yoshiyuki on the Casio 2022/5

Sometimes playing solo (with or without the presence of other humans within earshot) is an act engaged in with sacred intent, in which the subjectivity of a human ‘musicking’ agent is subsumed in an understanding of the presence and agency of deities. In quotidian life, however, most musicians must pay attention to other musicians – worldwide, instrumental playing to accompany the voice, or in ensemble with other instruments is probably more common than solo playing. One must collaborate, adjusting one’s own instrumental sound, dynamics and tempo to those of others, and sometimes also following the directives of a conductor. Put another way, even if we limit consideration to the playing of instruments (not singing), music as a social/interactive experience is more common than music in solitude. And what results from the serious playing of instruments together - in duets, trios, quartets, and ensembles of all kinds including guitar bands, wind and brass bands, gamelans, kumidaiko, matsuribayashi – is a special skill in listening and “moving” the music along together with the other players. In musicology it is called ensemble performance practice, and can be described in terms of minute details of the music each player produces, specifically with respect to realtime split-second positioning, shaping and adjustment of sounds in response to the other performers. It is one of the most mysterious but important phenomena “in play” when people play instruments together, and when a performance has gone well – be it by a duo, a large ensemble like a Javanese gamelan or Western orchestra, or groups of any dimension in between – there is an afterglow of sheer communitas, a wholehearted sense of fulfillment (some would call it joy) that may or may not be openly expressed, yet can linger for many hours.

And of course, beyond the musicians whom we play together with are the listeners. We perform for many hundreds of seated audience members in a concert hall, for potential listeners and dancers outdoors in a park or indoors in a pub or club, or for a single person on the other side of our living room. What of musicians’ attitudes to listeners? For some perhaps it is enough to “place” their sounds in proximity to listeners, apparently ignoring the effects of what they are doing; there have been many world renowned performers who have seemed almost indifferent to audiences. Yet, they have behaved like that in the knowledge that “sonic pleasure” will result, reaching and affecting listeners, provided only that the instrument is played with skill and devotion. If so, the performer herself can relinquish responsibility for verbal, visual or any other non-musical form of communication with listeners. There is an altruistic orientation toward listeners inherent even in such seemingly aloof performance, but it is entirely manifest in the quality of the playing.

Even without the verbal component of song, musical performance is a gift to all who really listen – not just ‘hear’ the sounds, but listen with willingness to give themselves body and soul to the music, to be immersed and swept away, which is to say to fully receive the gifts afforded by instruments, and proffered by the performers.

i For now I will exclude the human voice, simply because our voices most often produce words in song, thereby fusing semiotic systems whose simultaneity exponentially complicates matters of meaning, intentionality and reception.