Less than a minute’s walk from Wakamatsu-kawata station on Oedo Line is a mingei shop called Bingoya. The whiteness of the wall in the front resonates kura-zukuri and the sheer squareness of the building does not easily open its threshold to passers-by. I was one of those who would walk up and down in front of the shop without being able to stop at its entrance, which appeared to lead to a cave, far darker than the street.

Once my feet turned to the cave with no hesitation. It was not a particularly special day compared to other days. If there was anything special about it, that day I felt awkward talking to people. There are times when what we take for granted, what we accept as part of our everyday lives, suddenly becomes unbearable. It was probably that sort of day. I was unable to receive kind words from others. Infuriated and out of place, I did not know how to handle myself. Perplexed, I could only shy away from the care from others. No word could communicate this. No. No words could ever express this. Nor am I willing to express. I saw in myself whirlpools formed, sucking in and out what no words can do.

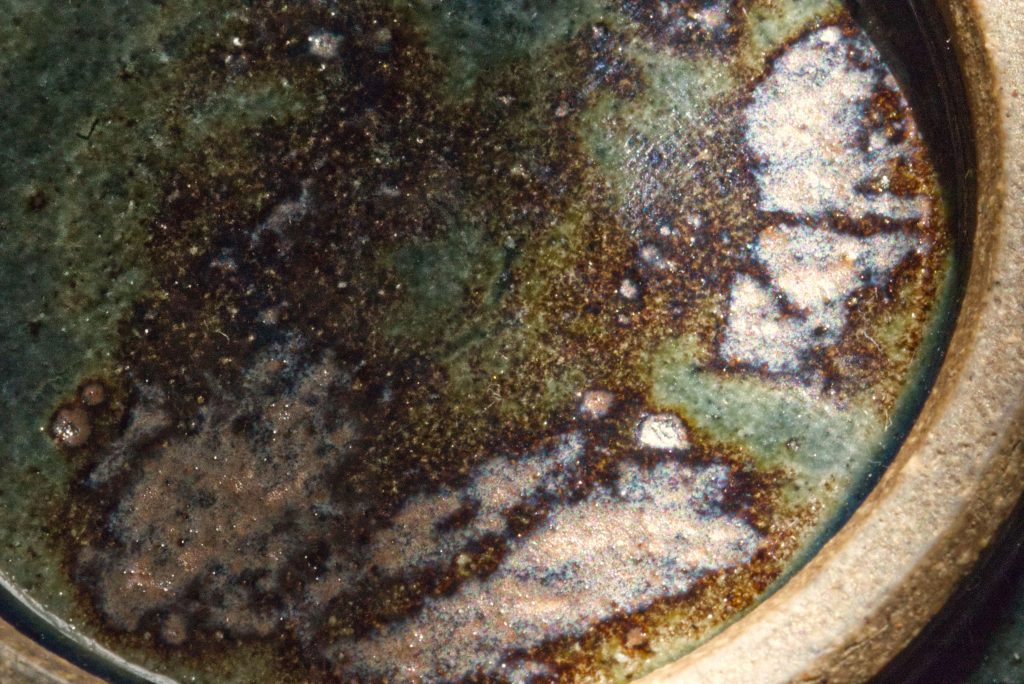

As I stepped in and saw someone at the till, I felt awkward and quickly went upstairs. By now, I was drawn to a blue tableware displayed by the wall on the left. It was a round dish with a gradation of blue, darker in the centre, lighter on the rim where blue was more like a spring sky with a thin layer of clouds, or a bloom of a white violet with a shade of pale purple. As the gaze glides over the rim, warmth arises and flows down towards the center, where a green shadow appears. It is water, my instinct responds in silence.

“Hold it in your hand and have a good look at it”.

Petrified by a sudden call, my body unconsciously turned towards the source of the voice. A small elderly man sat apologetically at the corner of the room. Behind his spectacles with their big round frames of a style once popular, his gesture urged me again to go ahead.

“Thank you.”

I was now made aware of someone in my presence, of his gaze and voice. I took up the plate with my right hand and turned it over to place it on the left palm. There was a whorl in the center.

I asked him what it was, to which he replied it was the making of natural glazing. A piece of pottery is made from local soil which contains a number of minerals formed over a long period of time, millions of years. Shaped and glazed over, it was placed in a kiln where direct fire grows and transforms from red to white heat, pushing up the temperature inside the kiln above 1,300 degrees Celsius. Some minerals sizzle, melt and flow, merging with other streams, more chemical reactions, and crystallize in inexplicable patterns as they cool down. Fire is carefully controlled but these reactions or patterns are the making of nature which result from the changing conditions of the day, including humidity, temperature, and weather. Natural glazing is a product of the combination of the local soil, water, air and fire.

I did not know why. It felt as if that plate was scooping me up somehow.

When this plate ‘seized’ me, did it appear to me as a mono/thing? There is no question a plate is a mono. It does not sustain its life by its activity. It is made by humans and for humans; it serves our everyday life. Nevertheless, part of me refused to call it a mono. Why?

Though it is difficult to find a clear idea, there are a few reasons I can think of.

First, the word mono reminds me of a finished product. It is produced exactly as the blueprint of the design, its colour and shape perfectly controlled and its smooth surface without minor scratches or stains. It is packed in a box and presented as something new. Conversely, there is something unbalanced about natural glazing. It is shaped according to the design but its beauty lies in differences among individual items. Experienced masters can guess the patterns of natural glazing drawn by their own kiln. Yet, they cannot be planned ahead as, after all, they are the making of natural conditions beyond our control.

In addition, the word does not match the circumstances in which I encountered this plate. I did not go into the shop to find natural glazing; it was just serendipity. I responded to it as if it had been offered to me as a gift from the non-human world. Generally speaking, the Japanese language avoids the literal and materialistic mono as a word to refer to something we give to someone. Mono we give as a present becomes okuri-mono. When we receive okuri-mono and share it with others, it is called osusowake/a portion, not amari-mono/something extra or left-over.

Most of all, the timespan of natural glazing exceeds the time involved in “making” by humans. If I define mono as what humans make, the plate is indeed mono. However, minerals have their own temporality and they take a much longer time to form themselves than “things” or “items of human making”. In order to refer to natural elements including minerals, water, earth, fire, air, we use the word “matter” but not mono/thing.

My task was to write an essay on mono/thing but I ended up writing why I did not want to call “a thing” what I had originally considered as mono. Yet, this is perhaps not a meaningless error.

For example, DNA analysis is a human deed, but DNA is not what humans have made. It is not mono in this sense. Yet, I have a feeling that we have already begun talking about DNA as if it could be artificially modified as mono. Science and technology are the mightiest measurement tools of human beings and their development/extensions incorporate what is non-mono into the intricate associations of the stories of mono[1] (s). Our technology has continued to extend its own measure, by trying to track down the origin of life on Earth, to identify connections between living and non-living organisms, so that it can weave astonishing stories about the unimaginable time length of 4.6 billion years. However, we should not place too much confidence in our ability to extend our measuring. When humans can measure nature and understand what it is, there is also anthropomorphism involved, shaping non-mono as mono, what humans make. It is worth acknowledging the nature of our measuring, and indeed our measurements.

Furthermore, there are cases where the “thing” produced by humans has exceeded its own limits of making. One of them is nuclear waste. The documentary film Into Eternity (2009) illustrates the facility called “Onkalo”, the final repository of the waste from a variety of aspects. What is intriguing in particular is the discussion about how to pass down the information about this facility to future generations for 100,000 years until the waste becomes harmless to living organisms. How long would 100,000 years be? In the present, the oldest human history that we can access by deciphering letters is 9,000 years ago at most; the Phoenician alphabet system which is the origin of alphabet letters today was devised 3,000 years ago. This indicates how unimaginable humanity 100,000 years in the future would be.

“Man is the measure of all things” (Protagoras). It is only by leaving this premise untouched that human “making”, which we call science and technology, were able to enjoy this level of development. However, some of the “things” made by human measurement today exceed our measuring, and we are trying to find ways to control them.

What I saw in the natural glazing was the potential coincidences made by nature, and the ungraspable timespan of minerals. My encounter with it was not the result of animism that identifies soul in the soulless, nor nostalgic feelings harking back to the mineral past of the Earth. It was just its materiality that I seized by chance – the materiality that resulted from the time minerals had spent in soil and chemical reactions that had surfaced on the plate. I do admit my imagination is indebted to the measuring provided by science and technology. At the same time, my feeling is that the encounter with natural glazing offered me a temporary leave from human measuring, which is never easy for us to let go.

(Translated from Japanese)

References (in Japanese)

ハンナ・アーレント『人間の条件』志水速雄訳、ちくま学芸文庫、1994年.

篠原雅武『「人間以後」の哲学:人新世を生きる』講談社選書メチエ、2020年.

森分大輔『ハンナ・アーレント:屹立する思考の全貌』ちくま新書、2019年.

マイケル・マドセン「10万年後の安全」(2009)、https://www.uplink.co.jp/100000/

Kiuchi, Kumiko. “Natural Glazing”. SNOW lit rev. no.9 (2020).